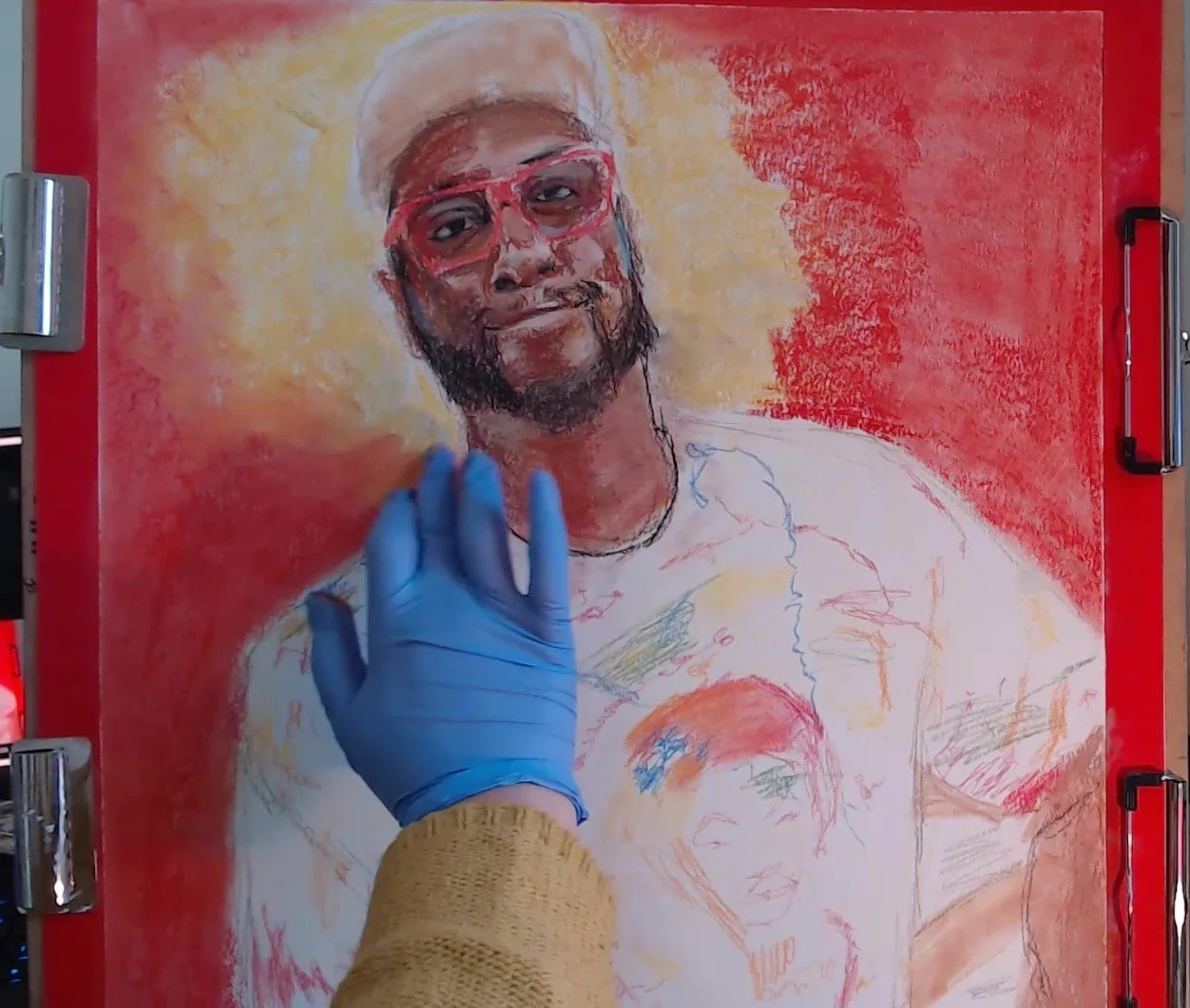

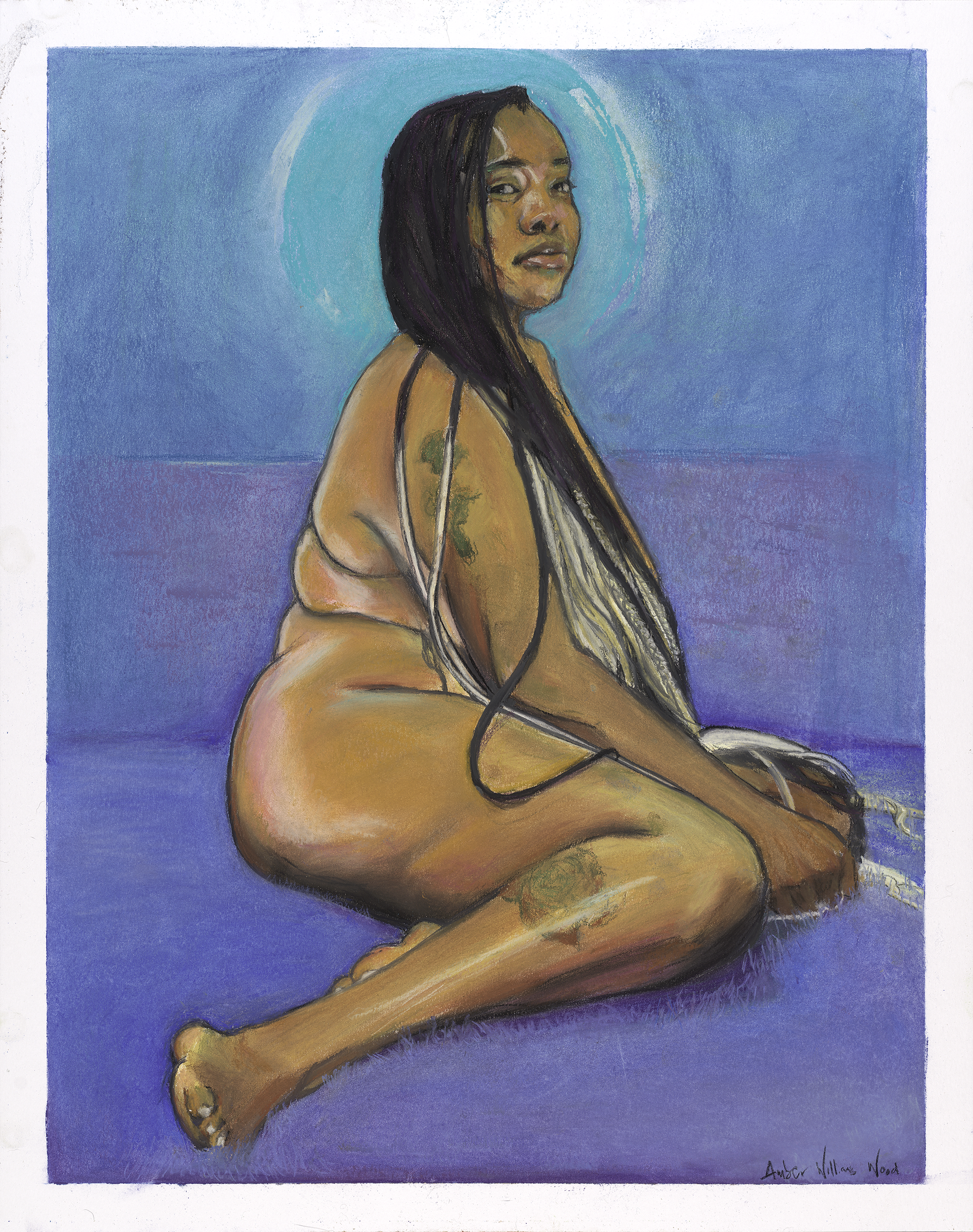

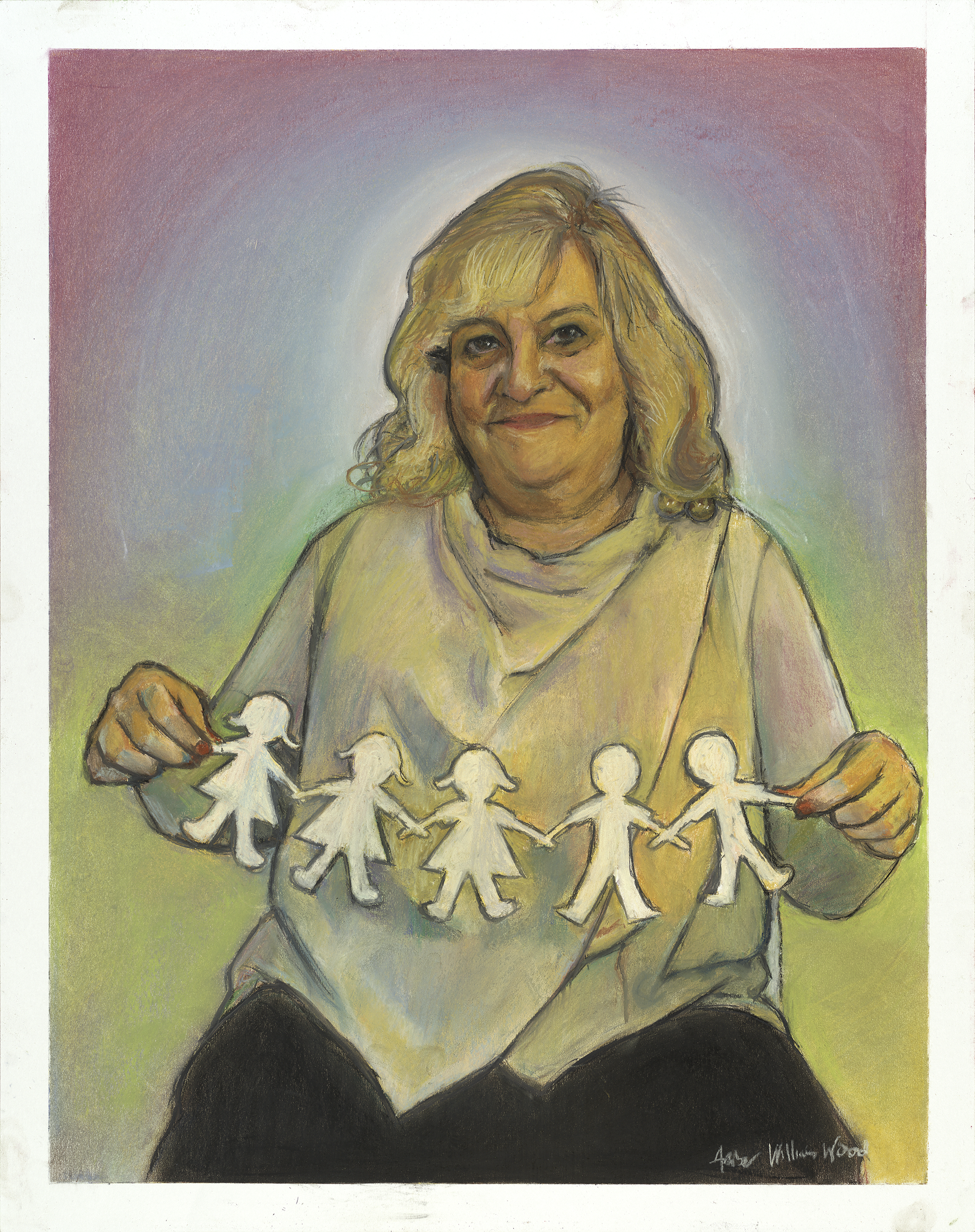

Fellow Worker

My goal in this series was to humanize fellow workers in expressive and impactful pieces that embrace my subjects with humor, earnestness, and revolutionary love. I wanted to give them an encapsulation of a moment in their lives, which not only made them feel seen and loved as whole people, but provoked an audience to see the subjects and themselves in that same way.

“The worker sinks to the level of a commodity and becomes indeed the most wretched of commodities; that the wretchedness of the worker is in inverse proportion to the power and magnitude of his production; that the necessary result of competition is the accumulation of capital in a few hands, and thus the restoration of monopoly in a more terrible form; and that finally the distinction between capitalist and land rentier, like that between the tiller of the soil and the factory worker, disappears and that the whole of society must fall apart into the two classes – property owners and propertyless workers.” (Marx)

It was particularly interesting and important to me to undermine the voyeuristic, exploitative default of both the camera and the historic portrayal of the worker. I wanted to give the subjects autonomy and power over these pieces, and make them not only collaborative, but an exchange with the viewer as well.

I collaborated with classmates to stage photoshoots with the subjects, with them at the lead of their narrative direction. I asked each to come to the shoots with the clothes, pets, and items, that made them feel most beautiful, and most themselves.

In a subversion of the royal portraiture of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, with their visual language of gratuitous hunting hauls, absurd collars, and ludicrous parliamentary robes, I sought to give the same care and power of narrative to my fellow workers but render them in a way that brought them closer to the audience rather than elevating them artificially above it. I wanted other workers to see themselves and the people they know and love in these pieces.

In the role of the worker, we sell first our time, then our lives, and increasingly ourselves. The US economy is primarily a service economy, where the majority of workers provide some kind of customer service; retail, food, sales, media, transportation, health care, and so on. In service work, emotional labor takes a toll, with workers compelled to “enhance the status of the customer and entice further sales by their friendliness” with a performance of smiles and pleasantness completely at odds with the internal state of stress, misery, poverty, fear, and resentment.

In the social media and surveillance age, we carry this emotional labor into every aspect of our lives; perpetually performing for the eye of the employer. We cannot be sexual or bawdy, we cannot be silly or irreverent, we cannot be sad, sick, or depressed. We cannot be overly excitable or celebratory. We are only permitted to be one thing: the usable, disposable, happy, hirable, fire-able, ever-ready worker.

I set out to create a space and time where these people could be seen, and see themselves, and inspire others to see themselves, as people, not things to be purchased, posed, traded, used. Here, to the degree I can give them the freedom to be it, they are whole; sexy, sentimental, strong, vulnerable, complex, shy, funny, tired, fascinating, playful, reserved, proud, modest, beautiful, complete.

My fellow workers.

If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

― Lilla Watson